Art of Darkness

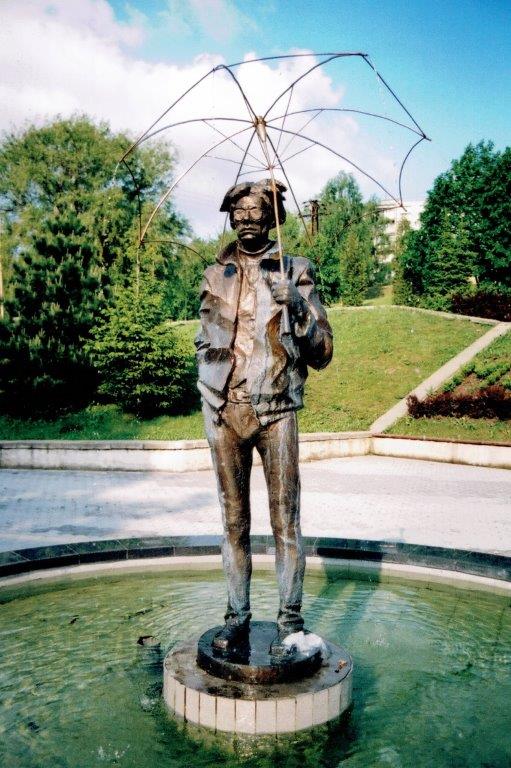

Mark Dapin emerges from Slovakia’s Valley of Death to find a shrine to pop culture – the Andy Warhol Museum.

Photos: Claire Waddell

It’s my girlfriend’s birthday and she wants to go somewhere special. “But Auschwitz is special,” I insist. She says she had something more romantic in mind. Women, eh?

I know just the place – the Valley of Death.

We are driving through Poland and the Valley of Death is on the Slovak side of the Polish border, about four hours south-east of Auschwitz. We cross the Dukla Pass into the Slovak Republic, where World War II tanks and guns stand sentinel in open meadows, a moment of battle captured in time.

Is that romantic enough for ya?

The Red Army drove the Nazis from eastern Slovakia in 1944 and more than 85,000 Soviet soldiers and 6500 Czechoslovakian troops were killed or injured fighting at the Dukla Pass.

The valley is rural, dark and beautiful; eerie, green and still. A Soviet fighter plane lies disabled on a hill, in a field of daisies overlooking a wooden church. Storks’ nests rest on telephone poles, like Cossack hats raised to the skies. Only cuckoo calls break the bucolic silence.

Well, only cuckoo calls and the stammer of clockwork eastern European cars clattering around the winding roads, spitting out moustachioed buffoons who climb all over the tanks while their wives take their photographs.

It’s not fair. I want to climb all over the tanks.

The war has not been forgotten in this place where so many died. A huge cement memorial outside the grim town of Svidnik bears undamaged carvings of local peasants hugging Red Army soldiers like brothers and a fresh wreath has been laid to the fallen.

There are two hotels in Svidnik. The first is full of drunken wedding guests and even-more-drunken musicians; the other backs onto a square where some kind of raucous gathering is taking place. I can’t tell if it’s a religious revivalist meeting, a sales promotion or a concert by the local equivalent of the Wiggles but I know I don’t want to listen to it all night.

We push on to Bardejov, with its lovely Renaissance and Gothic old town, where we rest before the morning’s pilgrimage to Medzilaborce, the cradle of contemporary art.

From the nearby village of Mikova came the family of the man who revolutionised the way we look at Heinz grocery packaging. He painted a portrait of a can of baked beans and a still life of a bottle of tomato sauce and sold them for thousands of dollars. He created an advertisement for Absolut Vodka. He is, of course, Paul Warhola.

Andy Warhol’s brother Paul, who retained the original spelling of the surname, has largely been ignored by the art world outside eastern Slovakia. Visitors to the Andy Warhol Family Museum of Modern Art in Medzilaborce, however, might well come away thinking he was at least as important as Andy.

Not that there are any visitors except me and my girlfriend.

The emphasis in the Andy Warhol Family Museum is on the family. Paul Warhola used to run a scrapyard in western Pennsylvania, before he retired to a chicken farm. He was a big bear in a trucker’s cap, with no hint of his brother’s fey fragility, and he began painting in 1989. While he followed the family tradition of silk-screen printing, he added a magic ingredient absent from his brother’s oeuvre: chicken feet.

Paul’s works include duplicated photographs of he and Andy, framed with chicken feet or obscured by chicken feet. He produced chicken-feet designs on ties and aprons and Aboriginal-looking paintings of white chicken feet on a black background.

Like Andy, he mocked the conventions of commercial art and portraiture. He did a series for Absolut Vodka, called Absolute Warhola, featuring repeated images of the vodka, the brothers and chicken feet.

At first Paul claimed he let his chickens make the markings themselves, creating random, unplanned paintings, like the Pollocks of poultry. It turned out, however, that he kept a pair of chicken feet in his freezer and used them as stencils. Left to themselves, apparently, chickens do not walk in pleasing patterns and they smear the paint.

Like Andy, Paul painted baked beans and tomato sauce but they are not very good paintings. To sell them, he was happy to sign them as “Andy Warhol’s brother”.

Even odder is the small section of the museum given over to James, a nephew of Andy and Paul and a children’s book illustrator who painted fantasy oils in the panel-van airbrush style – all maidens and dragons, candles and skulls. James often used Paul as a model for his illustrations, because Paul looked kind of medieval.

There is some genuine Andy Warholia in the collection, including enlarged photos of his baptismal certificate, his death certificate and, um, a bank statement – and a good gallery of prints, with a striking Red Lenin and a jolly Mao Zedong (mis-captioned “Mao C Tung”, as if his middle name was Charlie).

Andy Warhol never came to Medzilaborce, although both Paul and the factory “superstar” Ultra Violet have held exhibitions here. The local people were at first unenthusiastic about the museum, because they had heard Andy was gay, but the town recently won a $76,600 grant from the European Union to turn itself into “Warhol City”. It is not known whether the Warhol in question is Paul, James or Andy.

PS: We ended up spending my girlfriend’s birthday in romantic Hungary, but eastern Slovakia was better.

Destination Eastern Slovakia

HOW TO GET THERE

The cheapest, easiest way to get to the Slovak Republic is to fly to London, then pick up a discounted ticket to Prague, in the Czech Republic, with a no-frills airline such as Easyjet. From Prague, you can continue to the Slovak Republic by road, rail or air.

WHERE TO STAY

Pension Semafor, Kellerova ul 13, Bardejov, is one of the cleanest, friendliest, best-value guesthouses (about $38 a double room) in eastern Europe. From Bardejov, you can see most of east Slovakia in a couple of days.

WHERE TO EAT

Cafe Restaurant Hubert, Rad Nemestie 6, Bardejov is a fine restaurant/bar with excellent steaks (about $5.50).